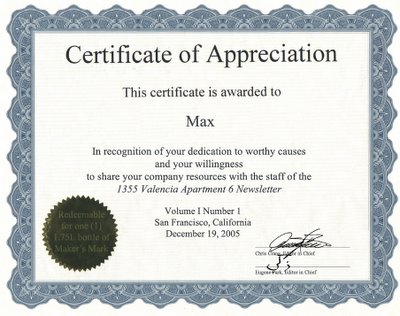

Crane and I get asked the following question a lot: When you’re not enjoying a day-hike in the Marin headlands or

volunteering your time to local youth groups, what are you watching on television?

Naturally our TV consumption includes the well-known staples: syndicated Seinfeld re-runs, Arrested Development (prior to its

premature demise), Scrubs, and Mr. Show with Bob and David on DVD or on TBS. Occasionally we mix in some Twin Peaks episodes

on DVD, and I have been known to pop in a Sports Night disc late at night when I’m by myself so I can watch specific stretches of dialogue

all S.P. (sans pants). And

any discussion of our favorite shows must mention Six Feet Under, Curb Your Enthusiasm, The Sopranos, The Daily Show, The Colbert Report, and The Office. Who among us doesn’t watch these shows?

Many of the programs we like most, however, do not enjoy such mainstream recognition. It is these that we will

focus on here in the hopes of winning these shows new converts.

It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia

In the midst of broadcasting its second season on FX, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia is our new favorite show. It

asks the question, “What happens when you take four self-involved post-adolescents who work at a dive bar in Philadelphia and have them

confront some of life’s serious issues like racism, cancer, abortion, child molestation, and Mid-East

politics?” The answer invariably involves a series of puerile decisions motivated by vanity, libido, or spite that inevitably leads to a

tragicomical comeuppance.

In the midst of broadcasting its second season on FX, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia is our new favorite show. It

asks the question, “What happens when you take four self-involved post-adolescents who work at a dive bar in Philadelphia and have them

confront some of life’s serious issues like racism, cancer, abortion, child molestation, and Mid-East

politics?” The answer invariably involves a series of puerile decisions motivated by vanity, libido, or spite that inevitably leads to a

tragicomical comeuppance.

It is hard not to sound trite in praising the show. It is offbeat and original and, it seems, under-appreciated. The darkly funny humor in each

episode belies—or perhaps befits?—the cheery air of the show’s ironic title as well as its theme music, an upbeat waltz whose fluttering flutes and

chiming bells render it anachronistic and laughably incongruous. Indeed, part of the punchline in certain scenes is the mismatch between the gleeful

soundtrack and the uncomfortable goings-on depicted on screen.

Real-life friends Rob McElhenney, Glenn Howerton, and Charlie Day occupy three of the five lead roles (Mac, Dennis, and Charlie, respectively) and

serve as the executive producers and writers of the show. Popular lore has it that the three friends produced the pilot that they shopped around to

networks for roughly $85 and that the three went from having sporadic work as actors to running a series on FX with full creative control after a

surprisingly short courtship period with the network. Kaitlin Olson deftly rounds out the core cast from the first season playing Sweet Dee, sister of

Dennis and bartender at the bar co-owned by the other three. Danny Devito joins the show for its second season as Dee and Dennis’s formerly absent but

now seemingly ever-present father.

While the topic at the center of (almost) every episode is a serious one deserving thoughtful discussion, the show makes no attempt to provide a

forum for such a discussion or to have a message of any kind whatsoever. It does not tackle, for instance, the issue of the Israeli-

Palestinian conflict as much as it makes light of it. Comedy, not commentary, is the show’s objective.

Every member of the core cast is a superb comedic performer, although the consensus in the apartment is that Charlie Day is especially hilarious.

The dialogue is riddled with peculiar idioms to a degree that suggests that, as is often the case with a close-knit group of buddies, the three friends

have idiosynchratic speech patterns they fall into with one another which they have wisely incorporated into their scripts. It seems that, with

each episode, at least one new meme is released into the mimetosphere to influence popular culture in the same way that the group vernacular depicted in Swingers induced countless teenage and collegiate men in the mid-nineties to describe things worthy of compliment as “money.”

It’s very likely that It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia is the funniest show you’re not watching on televison. So don’t be a bozo: start recording this

show on your TiVo, or on your DIY MythTV system, or on the inferior-quality DVR you received from your cable provider,

before this series goes the way of Arrested Development. Past episodes are available on iTunes, so you really have no excuse for missing out.

Related Links

The Prisoner

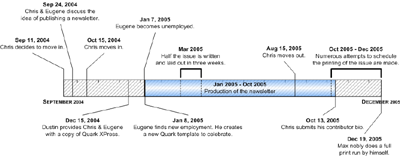

Originally broadcast in 1967 in the U.K., The Prisoner has recently had some of its episodes re-broadcast

on BBC America.

Originally broadcast in 1967 in the U.K., The Prisoner has recently had some of its episodes re-broadcast

on BBC America.

The premise of the show is simple on its face. The protagonist is a British secret agent during the Cold War who, upon resigning his post, is gassed

and kidnapped by persons unknown. When the agent awakes, he finds himself in a coastal resort town—in fact, a remote, secret prison facility—known

merely as the Village. The authorities running the facility want to know the reasons for the former agent’s resignation, but throughout the run of the series, the

prisoner never discloses his rationale, although he does at one point comment that he left the service as “a matter of conscience.”

In the bizarre details of the series, however, is where its appeal lies. Every prisoner in the Village is assigned a number, and the protagonist,

played by Patrick McGoohan, is referred to as Number Six throughout the show; his real name is never revealed. The exact whereabouts of the Village is

never disclosed. In one episode, it seems that the Village may reside on an island off the coast of Morocco; in another, it is said to be in the Baltic

Sea off the coast Lithuania. The Village is a fully functioning seaside town with prisoners holding jobs as shopkeepers, maids, taxi drivers, and the

like, many of whom dress in the de facto uniform of the Village which incorporates a motif of alternating motley colors vaguely reminiscent of a

harlequin’s costume. It is suggested in various episodes that the other denizens of the Village—that is, the other prisoners—are all former government

employees who possess confidential knowledge that must be protected. The only music ever played in the Village is the Souzaesque music of a marching band, and

the official emblem of the Village is, rather inexplicably, a penny-farthing

bicycle. The Village is run by the authorities, who are constantly monitoring the prisoners with hidden cameras that are installed throughout the

Village, and the chief authority goes by the name of Number Two. In each episode, there is a new Number Two, and it is never adequately explained why

the person filling the position regularly changes.

During the course of the series, Number Six continually tries to find a way to escape the Village, while the authorities doggedly try to determine

the true reasons behind his resignation using various interrogation techniques including psychopharmacological treatment, dream manipulation,

and general forms of deception and mindplay. As the series progresses, Number Six grows increasingly intent on discoveriing the identity of Number

One, the person presumed to run the Village. Interestingly, the dialogue of the show was carefully written such that the

existence of a Number One is never conclusively confirmed or denied by the authorities.

While its special effects and directing style may strike today’s audience as quite dated, the show’s surreal storytelling and

skepticism of established government were ahead of its time. What’s more, the thinly veiled anti-authoritarian message of the Cold War–era show, which questioned how far

the state can limit an individual’s liberty in the name of national security, still resonates today.

Related Links

Tom Goes to the Mayor

This animated show airs late at night on the Cartoon Network as a part of its Adult Swim line-up. It is executively produced by Bob Odenkirk, of

Mr. Show with Bob and David renown, and features cameo appearances by Mr. Show regulars David Cross, Jack Black, Brian Posehn, John

Ennis, Sarah Silverman, and Tom Kenny as well as by Michael Ian Black, Patton Oswalt, Jeff Goldblum, John C. Reilly, and Zach Galifianakis.

This animated show airs late at night on the Cartoon Network as a part of its Adult Swim line-up. It is executively produced by Bob Odenkirk, of

Mr. Show with Bob and David renown, and features cameo appearances by Mr. Show regulars David Cross, Jack Black, Brian Posehn, John

Ennis, Sarah Silverman, and Tom Kenny as well as by Michael Ian Black, Patton Oswalt, Jeff Goldblum, John C. Reilly, and Zach Galifianakis.

The animation style is really nothing more than a series of discrete still images displayed without any semblance of fluid continuity between the

stills. Characters in the world are rendered as highly pixelated images that resemble the shoddy purple output of a handcranked mimeograph machine.

TGTTM is too absurd

to describe in words and is an acquired taste, to be sure. Either you like

this sort of thing

or you don’t.

Related Links

The Venture Bros.

The opening title sequence to The Venture Bros. almost says everything

that needs to be said about the show. The animated show is an extremely well produced amalgamated homage to Jonny Quest, Scooby Doo,

the Hardy Boys, and superhero comics.

The opening title sequence to The Venture Bros. almost says everything

that needs to be said about the show. The animated show is an extremely well produced amalgamated homage to Jonny Quest, Scooby Doo,

the Hardy Boys, and superhero comics.

Far from a one-note satire intended to conjure boyhood nolstagia, The Venture Bros., at its best, relies merely on the absurdity of the

rich, farcical world it has created. The Venture family’s archnemesis, the Monarch, models himself after the monarch butterfly and the

lengths to which the comparison is taken can be so extreme that one almost needs a degree in entomology to get all the jokes. And the scenes

of the Monarch in the prison for supervillains are among our favorites from the series.

At times, however, the

show resorts to parody, but when it does, it typically does so with a degree of sophistication. Past episodes have incorporated everything from

cinematic allusions to Easy Rider and Chinatown to pop-culture references to David Bowie lyrics and the Internet-

famous antics of the “Star Wars Kid”.

Ultimately the show offers both smart comedy and diversion for a pop-culture savvy audience in the twenties-to-mid-thirties set.

It is currently in the middle of its second season and can be seen on the Cartoon Network during its Adult Swim programming.

Related Links

Moonlighting

In my mind, Moonlighting is the premier television dramedy.

The series ran on the ABC network from 1985–1989, and no other show I’ve encountered since has gotten the drama–comedy format right—that is, with the exception of the show I consider its

rightful heir, Sports Night, as well as, I hope, that show’s indirect descendent, Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip.

In my mind, Moonlighting is the premier television dramedy.

The series ran on the ABC network from 1985–1989, and no other show I’ve encountered since has gotten the drama–comedy format right—that is, with the exception of the show I consider its

rightful heir, Sports Night, as well as, I hope, that show’s indirect descendent, Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip.

The series starred Bruce Willis and Cybill Shepherd, who played David Addison and Madelyn Hayes,

the co-heads of and lead investigators for a private detective agency in Los Angeles.

Originally Moonlighting was commissioned as a so-called boy-girl detective show, a genre popular at

the time which included the contemporary series Remington Steele and Hart to Hart.

Charged with that assignment, creator Glenn Gordon Caron set out to craft a show loosely modeled

after the screwball comedies from the forties and fifties. Caron succeeded masterfully: the signature fast-paced, overlapping,

and often argumentative dialogue between Dave and Maddie has since been likened to the verbal

volleys found in classic Howard Hawks films.

Each week a new mystery found its way to the perennially feuding private eyes, but the detective component of each episode

usually functioned as a flimsy MacGuffin which arguably

did more to interrupt the action than it did to move it forward, given that the action of interest was the

interplay between the two lead characters. For the most part, there was limited or poor integration

of the mystery plotline and the duo’s argument-of-the-week. Contrast this approach with that of

Six Feet Under (one that seems to have been blatantly ripped off by Nip/Tuck).

In each episode, the HBO drama featured a new death, almost always of someone unconnected to the

undertaker brothers, Nate and David Fisher, yet the cadaver of an utter stranger—or, more precisely,

the story behind the body—would impart some lesson pertinent to the personal lives of

one or both of the brothers. The lack of synthesis between Dave and Maddie’s professional

and interpersonal drama yielded plots that felt fractured with forgettable

clients and time-wasting cases. Perhaps, however, this aspect of Moonlighting is merely

a sign of the times. While today’s television audiences may be accustomed to seeing

a story’s dramatic resolution and a character’s personal growth converge neatly even on sitcoms

nowadays—consider how frequently the answer to a medical ailment on an episode of

Scrubs conveniently provides the solution to the personal problem Dr. Dorian

happens to be struggling with at the time—this kind of storytelling, it seems, may not

have been nearly as common in the medium two decades ago.

The rapid-fire exchanges between Dave and Maddie

were the heart and soul of Moonlighting, although they were also

responsible for making the scripts over twice the length of the typical hour-long drama, a fact that contributed to the

infamous delays in the show’s production. Without the precedent of Moonlighting, one wonders whether the

the lengthy, staccato walk-and-talks on Sports Night, The Gilmore Girls, or The West Wing

would have been deemed acceptable a decade later. Granted, the historical impact the show had on the television industry

is an empirical matter that I myself am not in a position to know, but I do know that Moonlighting

had a seminal role in the development of my tastes and preferences, priming me for shows like Aaron Sorkin’s Sports Night and The West Wing as well as

Hawks’s His Girl Friday, a film now among my favorites that

I did not discover until the early nineties.

Just as my few remaining memories of the series from my schoolboy

days were drifting off into the ether, I discovered that

Lions Gate Home Entertainment had released the first two

seasons of Moonlighting on DVD last year. The third

season DVD became available this past spring, and the fourth

season is due out this September. One can only assume that

the fifth and final season will be out sometime next year.

Sadly many elements of the show have not held up over time,

and thus one must suspend a lot more than just disbelief

while viewing the episodes, but the aspects of the show

that made it good back then—the snappy banter, the “Will they, won't they?”

tension between the central characters—are as enjoyable as ever.

Related Links

The News Hour with Jim Lehrer

Forget network and cable new organizations. The News Hour on PBS is the most reliable and

thorough source of news on U.S. television.

Hands down. Most NPR affiliates broadcast

the audio from the show as well, and certain segments are available

via podcast.

Forget network and cable new organizations. The News Hour on PBS is the most reliable and

thorough source of news on U.S. television.

Hands down. Most NPR affiliates broadcast

the audio from the show as well, and certain segments are available

via podcast.

The only downside of having an hour-long program that offers detailed reporting on its stories is that

it seems that the coverage has depth at the cost of bredth. For a comprehensive summary of the day’s news,

viewers may consider looking to the BBC News World Service which, on our PBS station, immediately

follows The News Hour. Check your local listings.

Related Links

Stella

In the summer of 2005, Comedy Central aired the now canceled series Stella, which

starred Michael Ian Black, Michael Showalter, and David Wain, the members of the

New York–based comedy troupe of the same name. All three are former members of

The State,

and Showalter and Wain co-wrote Wet Hot American Summer.

In the summer of 2005, Comedy Central aired the now canceled series Stella, which

starred Michael Ian Black, Michael Showalter, and David Wain, the members of the

New York–based comedy troupe of the same name. All three are former members of

The State,

and Showalter and Wain co-wrote Wet Hot American Summer.

Whether one appreciates the comedy of Stella depends on what one makes of

the fictional persona of the trio the show creates. The characters of Michael, Michael, and

David are spastic man-children whose immature nature contrasts with their

grown-up, dressed-up garb. The three have been called

“modern-day

Marx Brothers”, and, accordingly, the misadventures chronicled in

the series are best characterized as antics, hijinks, and shenanigans executed

while dressed in suits. For some, the silliness may be insuperably off-putting.

However, while the three performers tend to play their scenes big and while their

characters in the show may fall on the side of zany, the men of Stella

generally avoid hitting the audience over the head with a punchline and are, first and foremost,

sharp comedians, who, in this particular show, just happen to portray three magnificently clueless buffoons.

There is an endearing innocence to Stella’s brand of comedy. No one gets hurt

when there’s no butt to any of the jokes (other than themselves); indeed, the men seem to have

a predilection for victimless non sequiturs. The only group

that may arguably receive some playful poking is what one might call the girlie-girl crowd.

The threesome seems to enjoy mocking some common girlish verbal affectations. While addressing

one another, they frequently preface their sentences with a quick and emphatic

“you guys,” “omigod,” or “can I say something though?” in the way one would expect

sorority sisters to speak. Then again, by doing so, the trio comes off

as drolly effeminate, so it is hard to say whether they are, in fact, deriding a particular

category of people or whether they are merely interested in adding yet another layer of absurdity

to their characters. Mockery or tomfoolery, the mode of behavior crops up throughout the series,

as it does in a scene when

the guys are committed to a sanatorium.

Whichever way one comes down on Stella, one has to admit that it has a

pretty catchy theme song.

Listening to this song always puts the residents of 1355 Valencia Apartment 6 in the mood for

some dumb comedy dressed up in a suit.

Related Links

Significant Others

This show may not merit a place on the list of top eight shows you may not know about,

but without a doubt, it is a show that you very likely did not watch during

its brief twelve-episode run on Bravo.

This show may not merit a place on the list of top eight shows you may not know about,

but without a doubt, it is a show that you very likely did not watch during

its brief twelve-episode run on Bravo.

The show was an interesting experiment in minimally scripted, improvisational comedy.

It offered more room for ad-libbing than Curb Your Enthusiasm, heavily

relying on the abilities of the performers, most of whom had exceptional comedic

instincts and timing.

The series follows the lives of three (eventually four) married couples living in Los Angeles.

The action jumps from couple to couple, whose social spheres are entirely separate

from one another. The only thing that links

them together is that they all share the same marriage counselor. Snippets of

the counseling sessions are interspersed throughout each episode and

are shot such that the actors are looking directly into the camera and

contentiously riffing off one another with, oftentimes, an

impressive degree of acumen.

When Crane and I stumbled on this show during its first season, we were pretty glad we found it.

That said, when it was quietly dropped by the network a year later, we failed to notice.

From what I can tell, the critical reception of Significant Others

was mixed at best. One of the positive reviews

I found online comes from the New Yorker, and it does a good job of

describing the show in greater detail than will be given here.

As one might expect, the final product of each improvised episode was a bit uneven.

The most consistently funny couple was Ethan and Eleanor, played

by Herschel Bleefeld and Faith Salie. Those two were the obvious stand-outs

from the cast with an honorable mention going to

Fred Goss, who expertly played the middle-aged husband Bill as a

listless, jobless, hopeless yet winsome schlub.

If you’re bored and frustrated with the quality of sitcoms today, then try

renting Significant Others for a nice change of pace.

Related Links

In the midst of broadcasting its second season on FX, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia is our new favorite show. It

asks the question, “What happens when you take four self-involved post-adolescents who work at a dive bar in Philadelphia and have them

confront some of life’s serious issues like racism, cancer, abortion, child molestation, and Mid-East

politics?” The answer invariably involves a series of puerile decisions motivated by vanity, libido, or spite that inevitably leads to a

tragicomical comeuppance.

In the midst of broadcasting its second season on FX, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia is our new favorite show. It

asks the question, “What happens when you take four self-involved post-adolescents who work at a dive bar in Philadelphia and have them

confront some of life’s serious issues like racism, cancer, abortion, child molestation, and Mid-East

politics?” The answer invariably involves a series of puerile decisions motivated by vanity, libido, or spite that inevitably leads to a

tragicomical comeuppance. Originally broadcast in 1967 in the U.K., The Prisoner has recently had some of its episodes re-broadcast

on BBC America.

Originally broadcast in 1967 in the U.K., The Prisoner has recently had some of its episodes re-broadcast

on BBC America.

This animated show airs late at night on the Cartoon Network as a part of its Adult Swim line-up. It is executively produced by Bob Odenkirk, of

Mr. Show with Bob and David renown, and features cameo appearances by Mr. Show regulars David Cross, Jack Black, Brian Posehn, John

Ennis, Sarah Silverman, and Tom Kenny as well as by Michael Ian Black, Patton Oswalt, Jeff Goldblum, John C. Reilly, and Zach Galifianakis.

This animated show airs late at night on the Cartoon Network as a part of its Adult Swim line-up. It is executively produced by Bob Odenkirk, of

Mr. Show with Bob and David renown, and features cameo appearances by Mr. Show regulars David Cross, Jack Black, Brian Posehn, John

Ennis, Sarah Silverman, and Tom Kenny as well as by Michael Ian Black, Patton Oswalt, Jeff Goldblum, John C. Reilly, and Zach Galifianakis.

The

The  In my mind, Moonlighting is the premier television dramedy.

The series ran on the ABC network from 1985–1989, and no other show I’ve encountered since has gotten the drama–comedy format right—that is, with the exception of the show I consider its

rightful heir,

In my mind, Moonlighting is the premier television dramedy.

The series ran on the ABC network from 1985–1989, and no other show I’ve encountered since has gotten the drama–comedy format right—that is, with the exception of the show I consider its

rightful heir,  Forget network and cable new organizations. The News Hour on PBS is the most reliable and

thorough source of news on U.S. television.

Hands down. Most NPR affiliates broadcast

the audio from the show as well, and certain segments are available

via

Forget network and cable new organizations. The News Hour on PBS is the most reliable and

thorough source of news on U.S. television.

Hands down. Most NPR affiliates broadcast

the audio from the show as well, and certain segments are available

via  In the summer of 2005, Comedy Central aired the now canceled series Stella, which

starred Michael Ian Black, Michael Showalter, and David Wain, the members of the

New York–based comedy troupe of the same name. All three are former members of

In the summer of 2005, Comedy Central aired the now canceled series Stella, which

starred Michael Ian Black, Michael Showalter, and David Wain, the members of the

New York–based comedy troupe of the same name. All three are former members of

This show may not merit a place on the list of top eight shows you may not know about,

but without a doubt, it is a show that you very likely did not watch during

its brief twelve-episode run on Bravo.

This show may not merit a place on the list of top eight shows you may not know about,

but without a doubt, it is a show that you very likely did not watch during

its brief twelve-episode run on Bravo.